Seals’ sense of rhythm may give us answers about our own musicality

New research from Aarhus University suggests that seals can both distinguish and react differently to different rhythms. A big step forward in understanding human musicality, says Associate Professor Andrea Ravignani.

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/2/5/csm_Andrea_og_saelem_17d4ca4f3d.jpg)

When a small child develops language, the language centre is not the only part of the brain that is activated; a sense of rhythm goes hand in hand with language development for us humans. The same also applies to birds. Monkeys, on the other hand, turn out to have almost no sense of rhythm. But in fact, researchers currently know very little about whether other vocally-plastic mammals, like us, also pick up on and react to rhythms.

However, a new study from the Centre for Music in the Brain at the Department of Clinical Medicine at Aarhus University and Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics now suggests that seal pups do not just listen to, but also react differently to sounds played in different rhythms.

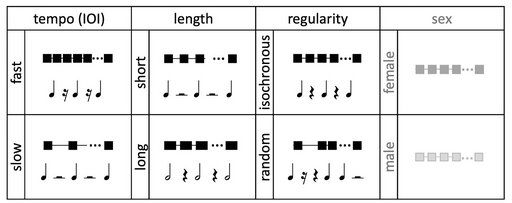

Associate Professor Andrea Ravignani is behind the study, in which the researchers tested a total of 20 harbour seal pups to see if they had an understanding of rhythm. Over a period of 30 minutes, the researchers played sequences of seal calls in different rhythmic variations and tempi. Some were quick, others slow, some were rhythmic, while others were irregular. The experiment showed that the seals reacted differently, depending on which rhythm the researchers played, says Andrea Ravignani.

“We filmed the seals’ reactions to the sounds and measured how many times they turned their heads to look at where the sounds were coming from. We then examined whether there was a difference between how many times the seals turned their heads, and how long they looked towards the sound, depending on the rhythm we played. This allowed us to see whether the different rhythms produced different reactions,” says Andrea Ravignani.

The method is also known from studies of babies’ reactions to sounds and rhythms, and although it may seem strange to investigate the rhythmic sense of seals, the study, according to Andrea Ravignani, may provide not only a better understanding of the seals’ sense of rhythm, but also of human language development.

“Our study represents a significant step forward in relation to our understanding of humankind’s own musicality and language development, about which we still don’t know very much today. By showing that another vocally plastic mammal can also perceive different rhythms, we support the scientific hypothesis that the two abilities are interconnected,” he says.

“We can conclude that even very young, untrained seals can distinguish vocalisations from other seals, based on their rhythms. It shows that we are not the only mammals to show rhythmic understanding and learn vocalisations. The two abilities may possibly have developed in parallel in both seals and human beings.”

More studies on the way

According to Andrea Ravignani, the study may be the first of its kind to link a spontaneous rhythmic understanding and the development of vocalisation in a mammal other than human beings. At the same time, it is worth noting, says Andrea Ravignani, that early in life the seal pups have a robust understanding of rhythm that has not been trained. The same intuitive rhythmic understanding is seen in human infants.

The study raises more questions, which the researchers hope to be able to answer in other studies, says Andrea Ravignani.

“Can seals detect rhythms in sounds other than seal sounds, such as sounds from other animals, or abstract sounds? Can they perceive more complex rhythms? Are seals unique in this, or do other mammals also have a sense of rhythm? And what are the biological and physiological mechanisms that support this ability? These are all questions to which we now hope to find the answers.”

Behind the research results

- Type of study: Observational study

- Partners: Comparative Bioacoustics Group, Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics

- External funding: Max Planck Research Group (MPRG)

- Link to the scientific article: https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2022.0316

Contact

Associate Professor Andrea Ravignani

Center for Music in The Brain, Department of Clinical Medicine

https://musicinthebrain.au.dk

Email: andrea.ravignani@mpi.nl

Phone: +31 682680558