New method for fingerprint analysis holds great promise

Overlapping and weak fingerprints pose challenges in criminal cases. A new study offers a solution and brings hope for using chemical residues in fingerprints for personal profiling.

Collecting fingerprints

- For over 100 years, fingerprints have been used in criminal investigations and remain the most widely used physical evidence.

- Most fingerprints found at crime scenes are not immediately visible to the naked eye. Investigators must therefore develop the prints, for example, by dusting surfaces at the crime scene with colored powder that adheres to the fingerprints and makes them visible.

- Fingerprints are then lifted from the surface—often using gelatin lifters, which are flexible rubber sheets coated with a layer of gelatin that absorbs the fingerprint.

A groundbreaking study has made it possible to extract much more information from fingerprints as evidence than what is currently achievable.

A new study from the Department of Forensic Medicine at Aarhus University is the first in the world to analyze fingerprints on gelatin lifters using chemical imaging. This could be crucial in criminal cases where current methods fall short.

Danish police frequently collect fingerprints at crime scenes using so-called gelatin lifters. Unlike tape, these lifters are easy to use and are suitable for lifting fingerprints from delicate surfaces, such as peeling wall paint, and irregular objects like door handles.

Once collected, the fingerprints are photographed digitally so they can be processed through fingerprint databases. However, traditional photography cannot separate overlapping fingerprints, which are often found at crime scenes. Very faint prints are also problematic. As a result, many fingerprints that could otherwise contribute to investigations unfortunately have to be discarded.

A fine spray of solvent

A solution is presented in the new study from the Department of Forensic Medicine at Aarhus University, recently published in the scientific journal Analytical Chemistry.

"We are presenting a method that has the potential to be integrated into the police's traditional workflow. If this happens, more fingerprints from crime scenes could be used and evaluated both visually and chemically," says postdoc Kim Frisch, who is behind the study.

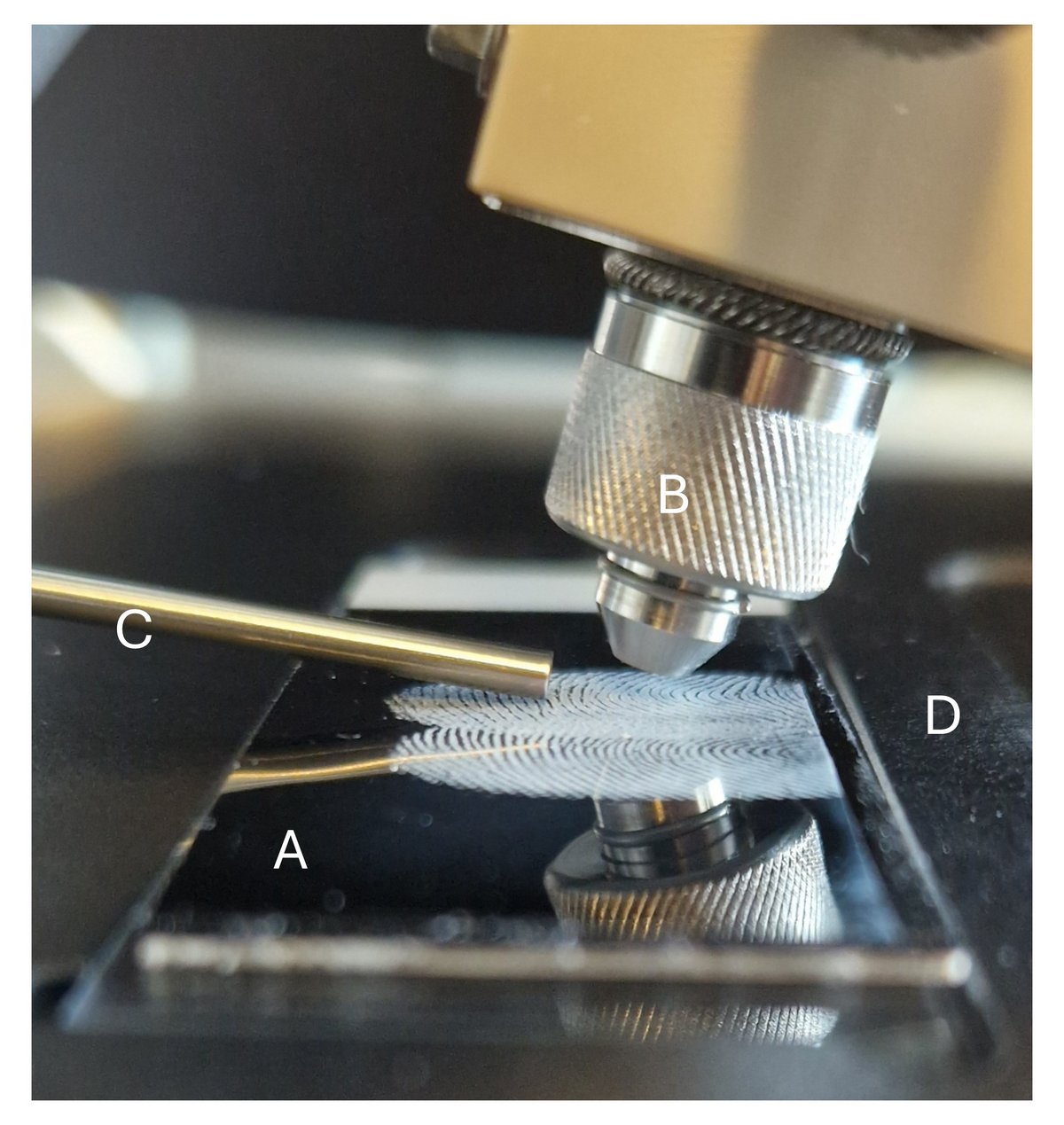

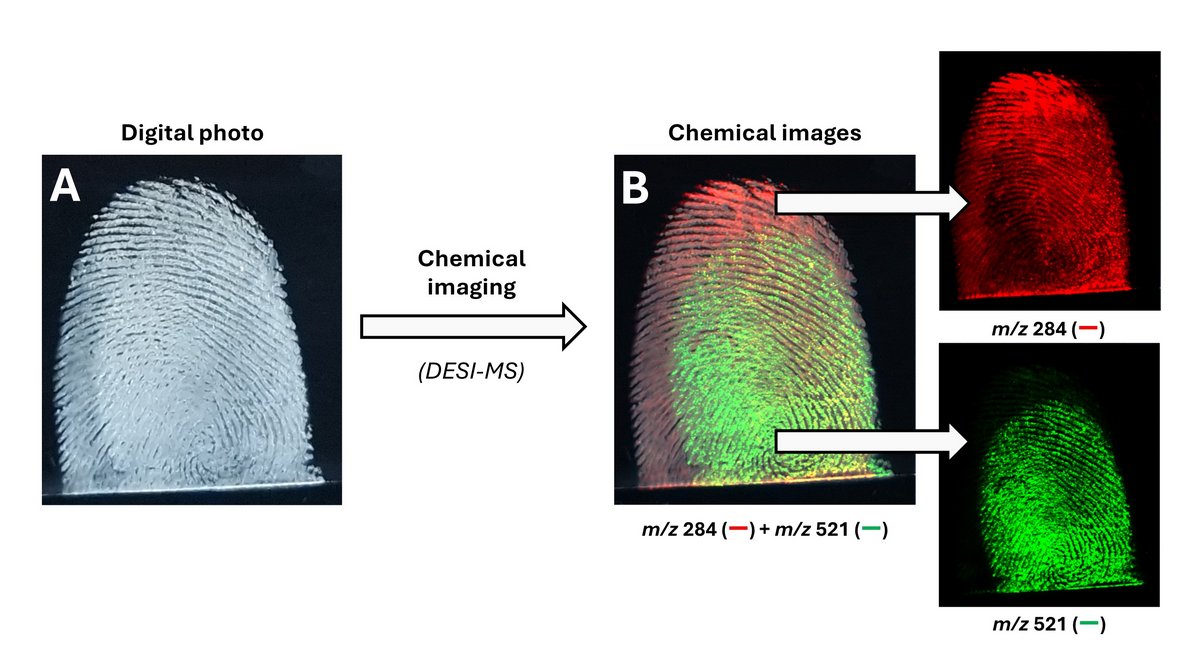

The method is based on a technique called Desorption Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry (DESI-MS), which works by measuring the chemical compounds in fingerprints based on their mass.

"We send a very fine spray of solvent, consisting of electrically charged droplets of methanol. This releases and ionizes substances on the surface of the fingerprint on the gelatin lifter. The substances are then drawn into the instrument, where their masses are measured individually," explains Kim Frisch.

DESI-MS was invented about 20 years ago and was developed for general surface analysis. In 2008, it was shown that the technique could be used for chemical imaging of fingerprints on glass surfaces and tape.

"But now we show that the technique can also be used to analyze fingerprints collected on gelatin lifter, which are used by police in many countries, including Denmark. This is analytical chemistry used in a forensic context, and it has great potential," says the researcher.

Revealing fingerprints where traditional optical imaging fails

Overlapping fingerprints pose a significant challenge for investigators because they are difficult to separate. The study shows that the new method can be used to separate overlapping fingerprints (Figure 2) and to enhance faint fingerprints in situations where optical imaging fails.

So far, the method has been tested on fingerprints lifted in the laboratory, but the researchers are now testing the method on fingerprints from crime scenes. For this purpose, they have received fingerprints collected by the National Special Crime Unit of the Danish Police , and there are high hopes for the results at the Department of Forensic Medicine.

Can we analyze gender, age, and dietary habits?

The method is still under development, and the researchers are now focusing more on analyzing the chemical composition of fingerprints.

A fingerprint is much more than a unique pattern—it also contains a variety of chemical compounds from the person who left the print. These compounds include natural lipids, amino acids, and peptides secreted from the skin. However, the fingerprint can also contain nicotine, caffeine, drugs, cosmetic ingredients, and potentially incriminating substances such as lubricant from condoms and explosives that have been secreted through the skin or contaminated the skin upon contact.

Chemical imaging could potentially be used for profiling the person who left the fingerprint.

Many researchers around the world are working to develop methods for this purpose—not only using the technique employed at the Department of Forensic Medicine in Aarhus. There are examples in the literature that fingerprints can reveal whether people have ingested or touched substances of abuse such as cocaine, cannabis, and ayahuasca.

Studies have also been conducted with the aim of determining individuals' gender, age, and lifestyle factors such as diet, medication, and smoking from their fingerprints. The Department of Forensic Medicine continues to work on the study, supported by the Danish Victims Fundand ongoing for two and a half years, in an effort to maximize the information that can be obtained from fingerprints.

Research focused on practical application

The research is conducted in close collaboration with the National Special Crime Unit of the Danish Police because it is important that the work is aimed at practical application.

So far, the results suggest that the method could be used in practice.

"When the police collect fingerprints at a crime scene, the gelatin lifters can, in principle, be sent to the Department of Forensic Medicine, where we scan the samples. However, the scanning process is time consuming, which means that we would not be able to analyze samples in the hundreds, as we do with, for example, blood samples. We expect that the method will be used in the future as a special analysis in more serious cases such as murder and rape," says Kim Frisch.

Behind the Research Results

- Study Type: Method Development

- Collaborative Partner: National Special Crime Unit, Danish Police

- External Funding: Offerfonden

- Read more in the scientific article: Desorption Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry Imaging of Powder-Treated Fingermarks on Forensic Gelatin Lifters and its Application for Separating Overlapping Fingermarks | Analytical Chemistry (acs.org)

Contact

Postdoc Kim Frisch

Aarhus University, Department of Forensic Medicine

Phone: +45 87 16 75 45

Email: kfri@forens.au.dk